In the storm of a pandemic, Community Servings heals with food

BOSTON — In 1990, when the country was gripped by a deadly virus that triggered an explosion of funerals and stirred ragged hopes for a miracle drug, one great mercy was delivering food to those who were sick.

“People were suffering from AIDS Wasting Syndrome,” David Waters, the CEO of Community Servings, explains of that plague. “Your body essentially attacks itself, trying to kill the virus, and you don’t ingest enough food, so you waste away.”

There were no drugs. People who were dying of AIDS seemed to get thinner by the day. “The only way to care for people you loved was to feed them.”

In the midst of that crisis, Community Servings was born, a small, Boston-based nonprofit meals program that prepared from scratch and delivered medically tailored hot food to people who had HIV/AIDS. Their tagline: Food Heals.

Thirty years later, there’s a new virus, but the same battered hope for a cure, and the same need for food. To meet the new crisis, Community Servings has increased its meal production by 45 percent since early March. The agency is currently preparing 14,500 scratch-made meals per week for chronically and critically ill individuals with the support of donations and grants from organizations, including the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation. And in June, the organization reached a major milestone, the production of its 9 millionth meal.

“It does feel like we’ve come full circle,” Waters adds. “We were born out of one pandemic, and that has prepared us well for this one. It reminds us how important the work is and why we still get up and leave the house and come to work.”

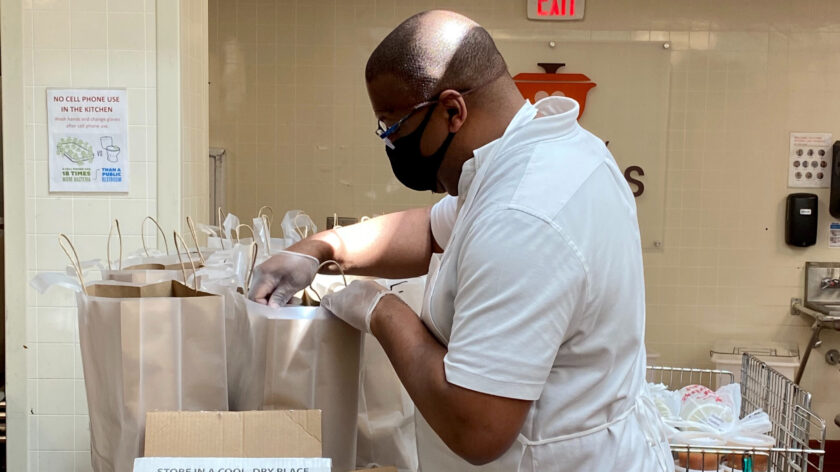

The small organization has overcome significant challenges as it has ramped up services in the midst of an unpredictable pandemic. When COVID-19 first hit, staff members at Community Servings were afraid. Within the course of a day or two, seemingly absurd ideas – gloves, masks, temperature checks – came to seem obviously practical. Office staff went home and worked remotely.

The corps of 75 volunteers — who help the kitchen team at Community Servings cook the food that is delivered – mostly disappeared. “That was like losing 35 full-time staff members in a week.”

As the state’s COVID-19 policy emerged, Waters didn’t know if Community Servings would be declared an essential organization. Without that designation, Community Servings would have to shut down and stop providing clients with food.

To protect against this, the organization put together 2,000 emergency pantry boxes of shelf stable foods. “We wanted to make sure that people who were low income and extremely isolated and compromised, had something in their pantry. We sent them two boxes to represent two weeks’ worth of calories – not as appetizing as the food we would make, but it meant they wouldn’t starve.”

Waters was relieved when Community Servings was declared “essential” – yet that created new challenges. His team needed to deliver more meals and become safety experts, processing the flow of information from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The priority: keep clients safe; keep staff safe.

“We do contact tracing for anybody that is coming in, whether that’s staff or volunteers or the plumber,” Waters says. “Every day, we know who’s in the building and what their contact information is in case we had to go back and alert people about an exposure. We’re also sanitizing and taking temperatures of everybody every day.”

Like Massachusetts, New York, and other states, Community Servings was also scrambling to find personal protective equipment. The organization already used gloves, but it had to find more. “We scoured the web, and we ordered some. And we had our board members go to each of their dentists. One dentist would give 100 disposable masks; another dentist would give 100.

“We also went to the Boston Mask Initiative and got 300 donated fabric masks for each member of our staff.”

Community Servings had already been planning to expand, but COVID-19 forced a dramatic growth spurt.

“We have a relatively new program where health insurance companies are hiring us to feed their sickest patients. We just didn’t anticipate that we’d be doing this in the middle of a pandemic.”

On March 1, when COVID-19 was still a headline, Community Servings was delivering 10,000 meals a week. By May, that number had jumped to 15,000 and that pace of growth is expected to continue. On top of this, Community Servings is supplying the City of Boston with another 3,000 meals a week that are being distributed to homeless shelters, senior centers, and organizations like the Boys and Girls Club.

It was the kind of growth that Waters had thought would take three years. To finance this growth, Community Servings created a rapid response fund.

“What we received from the McGovern Foundation and other generous partners is allowing us to hire more staff, buy more food, meet the extra requirements for sanitation and safety, and significantly ramp up our operations,” Waters said.

The other funders include the Boston Resiliency Fund, Bank of America, Biogen, the Janey Fund, the Manton Foundation and gifts ranging from $10 to $100,000 from generous individuals.

“We’re seeing a much greater interest in our work. Because people can see the direct connection between hunger and health,” Waters says.

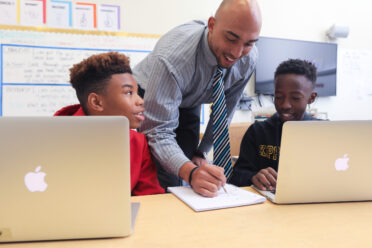

One casualty of the pandemic was Community Servings’ food services training program, a successful initiative that also helped people find food service jobs. Sadly, as COVID-19 shuttered so much of the state and the country, the program was temporarily put on hold. As a result, Community Servings spread out a big safety net, hiring ten of the program’s past participants to support its growth.

“We trained them,” Waters says, “so we knew they were talented.”

What’s next? While the future is vividly uncertain, Waters does have a vision for right now.

“We see all of the things we’ve had to do to address COVID as being the new reality. We’re going to continue using masks. We won’t be able to have large volunteer groups for a year, and it could be months before we can restart our training program.

One thing won’t change: The meals will go out.

“Every meal is a gift to somebody who’s very scared and very sick and isolated, and it’s our job to help the community deliver these gifts.”