How we’re improving healthcare for children in Burkina Faso

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared on the Cloudera Foundation website. In April 2021, the Cloudera Foundation merged with the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation.

by Wessel Valkenburg, Azia Merzouki

Jan. 12, 2020

In Burkina Faso, 4 in every 50 children die before age 5. In the developed world, that number is 4 in 1,000.

To save more children’s lives, the World Health Organization created a protocol that health workers in developing countries can use to streamline the physical exams of children under the age of 5.

Initially, the protocol was used in a fraction of all consultations. But when the Terre des hommes foundation (Tdh) started the implementation of the protocol on tablets project in 2009, usage of the protocol rose to over 90% of consultations, currently covering half of all health facilities in Burkina Faso. The digitalized protocol as a diagnosis assistant is so helpful to health workers that some communities even collected money to buy tablets to enable their healthcare center’s participation in the program.

The tablet not only helps with diagnosis and the recommendation of treatments, but also it is connected to the cloud and allows health authorities to monitor and evaluate the quality of healthcare. In other words, Burkina Faso, with the help of Tdh, can assess children’s health using a database with over 5 million consultations.

This is not where the story ends. This is where the next chapter begins.

With the help of Cloudera Foundation, we have been able to put together a team of data scientists, equipped with a cloud-based computing cluster running Cloudera’s software. The time is right for boosting the digital protocol with smart tools, notably based on data that comes from the subject population itself.

We have two objectives:

- Detect the most common errors in real time and give appropriate feedback to the health workers to improve their work.

- Enhance epidemiological surveillance with predictive models, which combine multiple sources of data, such as the locations of refugee camps, the weather, and more.

We started our journey with the Cloudera Foundation in early 2019. Until now, the biggest challenge had been to understand the data and assess its quality. Every data scientist can tell you that data cleansing is more than 80% of the work in any project. Here again, we experienced that truth. The application that the health workers use has been improving incrementally over the years. Inherently, the data records have changed and grown along with the changes. Then there were gaps in the funding of the project, which form gaps in the time periods we cover. Then there are fields in the data, for which imposing consistency with other fields, was only implemented in a later version. Then there is the fact that the number of regions participating in the project has been growing steadily over time. But because the implementers are our own people, we have been able to understand each of the factors that contribute to the shape of the data.

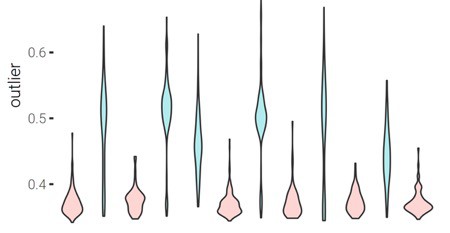

It is too early to draw conclusions about success or failure. But it is exciting that we have been able to classify health workers, based on their personal outlier scoring of consultations. For a consultation, its outlier score is a single number, which rates how common or uncommon the consultation is, relative to the entire set of consultations. The bare number is quite meaningless, but things become interesting when we look at the distribution of those numbers. If we consider all consultations, we see the distribution of outlier scores for the entire country. But every health worker has their own distribution, based on their consultations. By comparing these distributions, we can group health care workers by their behaviors and various populations of patients, as you can see in the figure.

The next step is to analyze, in collaboration with human experts, the underlying cause for these distributions. Some distributions may correspond to regional problems, such as malnutrition. Others may, and do (!) correspond to typical errors in the input by the health worker.

We believe that this analysis, only made possible by the joining of forces between Tdh and the Cloudera Foundation, very strongly suggests that we can further improve healthcare for children in Burkina Faso.

What’s up next? Aggregating multiple sources of data, train neural networks to detect correlations between outbreaks and other information, and save the world. Well, the third item will take a bigger effort than this project, but the first two certainly go in the right direction.

Wessel is a data scientist and data engineer at Terre des hommes Foundation.

Aziza Merzouki, PhD, is a data scientist and a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Global Health (IGH), University of Geneva (UNIGE).