How can we realize the value of data for small-scale agriculture?

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared on the Cloudera Foundation website. In April 2021, the Cloudera Foundation merged with the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation.

by Claudia Juech

Sept. 19, 2019

The Cloudera Foundation goes where data can make the most difference — irrespective of geography and subject matter.

One of the most promising fields for impact is agriculture. Around the world, massive amounts of data relevant to the agricultural sector are collected, including soil nutrient and moisture levels, meteorological conditions, aerial imagery of farm plots and crops, and, of course, the impact of these factors on market pricing. Data science has already transformed corporate large-scale farming and boosted productivity and profits by helping to determine optimal harvest times, ideal seed types and reduce reaction time to pests.

Agriculture is the world’s largest industry. In low- and lower-middle-income countries between 30% and 60% of the population are still working in agriculture compared to 1% in high-income countries such as the U.S. Many of the world’s more than 500 million small-scale farming families are entrenched in poverty and often also food insecure, despite their critical place in the food system value chain.

So why can’t the same benefits that corporate and large-scale farmers already reap from data technology be used in small-scale farming?

To explore this question, the Cloudera Foundation partnered with CGIAR, a global network of research organizations engaged in research for a food-secure future, and the Hoffman Centre for Sustainable Resource Economy to host a workshop of international practitioners, researchers and funders at Chatham House over the summer. We uncovered much potential, but not without drawbacks.

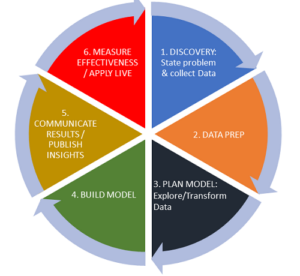

Looking across the different stages of the lifecycle of data, initiatives such as 50 x 2030 are already working on closing the gap in the collection of agricultural data in low-income countries. Additionally, sensors and satellite imagery are becoming less expensive over time, even though the upfront capital necessary to purchase, deploy, and maintain them remains a significant challenge for non-profit organizations and social enterprises working in this space.

Unfortunately, the collection of massive amounts of data is not automatically or immediately useful. It requires an intimate understanding of the specific problems individual farmers are trying to solve. The value of the data collection can only be realized if the resulting insights truly respond to a critical information need, are accessible to farmers (who often might not have internet access or a smartphone), and are possible and desirable for farmers to act on. One of the clear takeaways of the workshop at Chatham House was that the 500 million global small-scale producers are by no means a homogenous group. One possible next step is to develop a clearer picture of the different categories of small-scale farmers to identify which ones might be best equipped to make use of new data capabilities, e.g. farmers focusing on high-value cash crops as demonstrated by Grameen Foundation’s SAT4farming initiative. Workshop participants also discussed additional uses of agricultural data by governments and research organizations, which raises new ethical questions around the capture, storage, and processing of that data.

Inescapably, one of the most critical issues around big data collection that we must grapple with is environmental impact. Using data science to help farmers increase their yield could have adverse effects on their land or the surrounding ecosystem. Increasing plot sizes means removing trees and shrubbery, and over-tapping water aquifers for irrigation today means more arid conditions months or years from now. Thus, the use of data must also help us consider and balance the contraindications of our actions so that we may plan accordingly to mitigate these unintended consequences.

Fundamentally, I believe that bringing data science to agriculture — and for the benefit of small-scale producers, especially — bears the promise of transforming our global food system for the better. Doing so has the potential to make this system on which we all depend more profitable for those struggling to get by, and more productive for a growing global population within the limits of our planetary boundaries.

Claudia Juech is the Vice President of the Data and Society program.